We naturally flock to those who mirror our interests, beliefs, or personal traits.

This phenomenon called the similarity-attraction effect is supported by many studies in social psychology. However, experts don’t fully agree on why this happens.

To unravel the mystery, researchers tested whether the concept of self-essentialist reasoning serves as the underlying process. Published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, the findings show how we think can unite and divide us.

What is self-essentialist reasoning?

Belief in a core essence, one that shapes your identity and includes specific traits and attributes, is called “self-essentialist reasoning.” In a press release, Charles Chu, Ph.D., an Assistant Professor at the Questrom School of Business at Boston University, offers a vivid analogy to describe the concept:

“If we had to come up with an image of our sense of self, it would be this nugget, an almost magical core inside that emanates out and causes what we can see and observe about people and ourselves.”

Dr. Chu, along with Brian S. Lowery, Ph.D., of the Stanford Graduate School of Business, co-authored the scientific article “Self-essentialist reasoning underlies the similarity-attraction effect.” They argue this belief in a core essence plays a significant role in why we are drawn to people similar to ourselves.

The process is two-fold.

First, when someone encounters another person who shares something in common with them, they see that person as similar. They believe this similarity stems from a deeper, core essence that defines who they are.

Next, they assume this shared essence means the other person also shares broader views and understandings of the world, creating a sense of a shared reality.

To test this theory, the researchers conducted four studies involving a combined total of 2,290 participants.

Comparing big and small similarities

Decoding the dynamics of human attraction, the first two studies explored whether belief in a core essence heightened the appeal of others who share both significant and minor commonalities

In study 1, participants were asked about their views on social issues, such as abortion, capital punishment, gun ownership, animal testing, and physician-assisted suicide. After reading about a fictional person who either agreed or disagreed with them, participants answered questions about their belief in self-essentialism, their attraction to the person, and whether they felt a sense of shared reality with them.

In study 2, participants quickly viewed slides of blue and other colored dots, guessing whether blue dots were in the majority.

They were then labeled as either overestimators or underestimators of blue dots and told this trait was strongly linked to one’s personality. Later, participants assessed a hypothetical person who was either an overestimator or underestimator.

Disrupting belief in a core essence

Researchers aimed to undermine the process of self-essentialist reasoning to discover whether it would alter patterns of attraction.

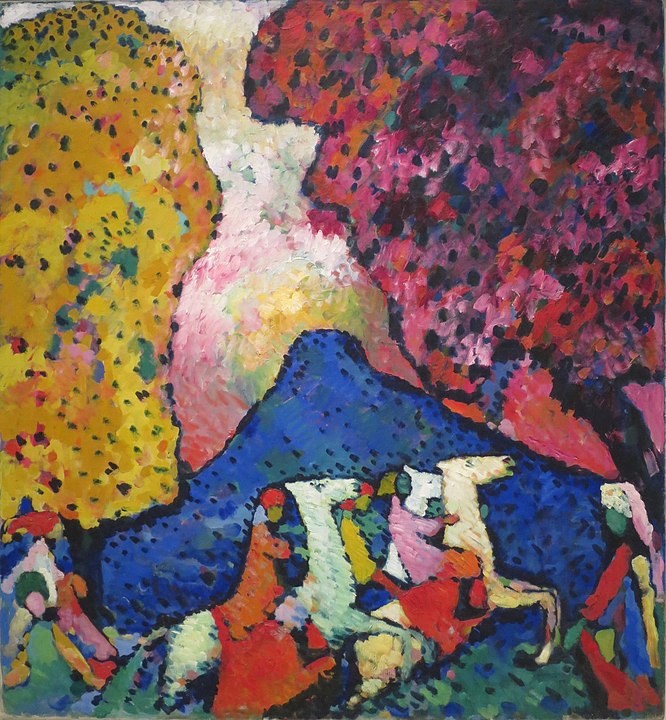

In both studies 3 and 4, participants completed an artistic preference test where they chose between pairs of paintings by 20th century artists Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. Based on their choices, participants were labeled either a Klee fan or Kandinsky fan.

In study 3, participants were divided into two groups: one was told that their artistic preferences strongly reflect their personality traits, while the other group was told there is no significant connection between the two.

In study 4, participants were randomly divided into three groups. One group was told using their core traits to guess others’ personalities can lead to mostly accurate impressions, while a different group was told it led to inaccurate impressions. In the control group, participants were simply told they would be giving their impressions of two people based on their preference for Klee or Kandinsky.

Next, both participants in studies 3 and 4 reported their level of attraction to hypothetical individuals who either shared or didn’t share their artistic preference.

The findings

These studies collectively reveal a fascinating trend: we are drawn to others because we see a bit of ourselves in them, through the process of self-essentialist reasoning.

Researchers found that people who strongly believe in having a core essence felt more attracted to others who shared even a single attribute with them, whether it was something significant or minor. This attraction is influenced by their perception of sharing a broader, common reality with those individuals.

However, when studies disrupted this thought process, the impact of similarity on attraction significantly decreased.

For example, participants in study 3 felt a stronger attraction to others with the same artistic tastes when they were told that such preferences were essential to one’s identity. Conversely, when artistic tastes were described as nonessential, the attraction still existed but was less intense.

In study 4, participants were less attracted to others with similar tastes when told that basing judgments on shared preferences leads to inaccurate judgments. They also perceived a smaller difference in a shared reality between individuals with similar and dissimilar preferences.

This confirms that how much we use our core traits to evaluate others directly affects our attraction to them. It also suggests that people can intentionally choose whether to apply this type of reasoning.

The power of similarity

Applying one’s core traits to assess others plays a key role in why we are attracted to people who are similar to us.

The research reveals that self-essentialist reasoning significantly boosts attraction and enhances perceived shared realities, underscoring the powerful role our traits play in forming social connections. Yet, it can also lead to superficial barriers, by magnifying minor differences into significant divides.

The authors recommend future studies further explore how automatic or conscious these reasoning processes are in people’s social interactions.

“What this work suggests is that we often fill in the blanks of others’ minds with our own sense of self and that can sometimes lead us into some unwarranted assumptions,” said Dr. Chu.

“When you hear a single fact or opinion being expressed that you either agree or disagree with, it really warrants taking an additional breath and just slowing down.”