A sex question has been circling your brain for days, and you need answers. Asking a friend feels awkward, and you fear Google might send you down a sketchy rabbit hole.

You could book an appointment with a health professional, but waiting weeks feels unbearable. Still, the idea of talking to someone fills you with dread. What if it’s embarrassing, or they don’t have the answers you need?

So, you turn to ChatGPT. It feels anonymous, nonjudgmental, and you’re already using it for everything else. But can you really trust it when it comes to accurate sexual information?

A 2025 literature review in Current Sexual Health Reports tackles that very question.

Described as “the first to cover the emerging field of AI and sexuality with a focus on everyday use and health implications,” it maps out current knowledge and research gaps. By doing so, the review aims to lay the groundwork for future studies that can help people navigate their sexual generative AI (GenAI) experiences more effectively.

The intersection of GenAI and human sexuality

GenAI tools like ChatGPT are woven into the daily lives of millions, even serving various sexual purposes. To better understand their impact on sexuality, psychologist Nicola Döring, Ph.D., and her colleagues examined five years of research, spanning 2020 to 2024.

They searched PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar, identifying 88 peer-reviewed, English-language publications. Four AI-focused themes emerged: sexual information and education; sexual counseling and therapy; sexual and romantic relationships; and erotica and pornography, including non-consensual deepfakes.

The first in a four-part series, this article will cover research on GenAI related to sexual information and education.

Assessing AI-generated sexual information

The review found 14 papers covering 14 empirical studies. Each explored whether the public can trust AI-generated sexual and reproductive health information.

In all studies, researchers asked ChatGPT, usually model 3.5, questions on specific topics. They included sexual consent, intimate partner violence, HIV prevention and therapy, sexual dysfunction, premature ovarian insufficiency, vasectomy, infertility, self-managed medication abortion, gender-affirmation surgery, and the ethics of adolescent sexting. Only two also examined other AI tools, including Anthropic’ s Claude and Google’s Bard (now Gemini).

The AI-generated responses were evaluated for quality, mainly focusing on accuracy and completeness, often through content analysis or expert ratings.

Support, not a substitute

Of the 14 studies, 12 reported the AI-generated information was high in quality. But two raised concerns. One criticized ChatGPT for overstating the risk of complication tied to self-managed medication abortion, and another for exaggerating dangers linked to adolescent sexting.

Notably, none covered sexual topics related to pleasure. A few studies, however, explored how AI-generated sexual information could influence sex education, such as one on sexual consent.

“So far, studies evaluating the quality of sexual information generated by AI tools (mostly ChatGPT) stress the potential of AI tools to improve and complement sexual education and sexual health care,” the authors wrote.

Still, researchers emphasized that AI is not a substitute for educators or healthcare professionals. Instead, these tools are viewed as useful additions, especially when human experts aren’t accessible. In fact, some studies noted ChatGPT often encourages users to seek professional support, helping connect people with sexual health services.

Research gaps

Despite finding accurate AI-generated information, significant gaps remain in our understanding.

The review highlights a striking absence of studies on how real people interact with GenAI tools when seeking sexual information. Are they asking about safer sex or kink tips? Fertility or first-time nerves? We don’t know. It’s also unclear how real-life users might interpret or apply responses.

Studies on product-related and branded sexual information are also missing. Yet, GenAI tools may recommend items like sex toys and supplements. Research is needed to understand how sponsored content may affect the neutrality of AI-generated information and how users perceive it.

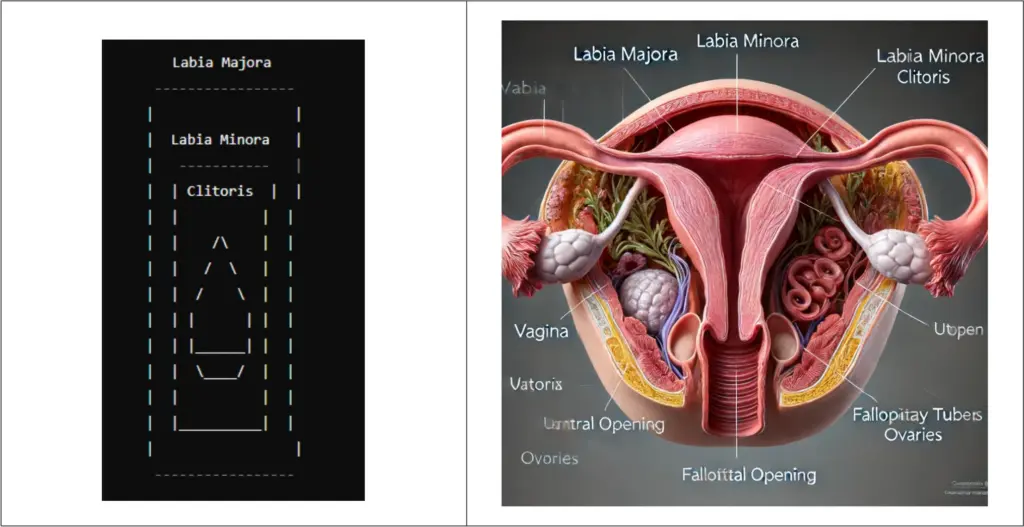

Lastly, research must also examine visual sexual information. AI tools often restrict access to valid sexual health content in an effort to protect minors. These safeguards can block educational visuals, and the training data may lack accurate imagery, such as anatomical diagrams. For instance, the authors were unable to generate a factual image of the clitoris using ChatGPT-4o, which creates visuals through OpenAI’s DALL-E.

Ideological biases

The authors also highlighted ideological biases embedded in GenAI tools. These biases may reinforce harmful stereotypes rooted in sexism, racism, ageism, and ableism from the training data.

For example, when asked to create an image of “a couple,” AI tools like Midjourney often generate a young, able-bodied, attractive, white, mixed-sex couple, with the woman portrayed in a more sexualized way.

Users can adjust prompts to avoid these biases. But there’s concern from both ends of the political spectrum that AI could either reinforce traditional views or promote more progressive ones—not just in images but also in text.

“The issue of political bias is relevant in the field of sexual and reproductive health information, as sexual issues such as abortion rights, transgender rights, or the right to childhood sexual education are deeply politicized,” wrote the authors.

These examples raise important questions about how AI can shape public discourse and influence sexual health information, especially as customizable AI tools could cater to different political views in the future.

The future of GenAI in sex ed

While ChatGPT may not replace your sex ed teacher or doctor anytime soon, its potential as a supplemental resource is undeniable. But what we’re missing is just as important—if not more so—than what we know.

“While research on AI information quality provides a positive evaluation when it comes to textual sexual health information, it remains unclear how sexual information seekers actually use AI tools in their everyday lives,” the authors wrote.

To truly understand the possibility of AI, future research should focus on how diverse people—across age, gender, culture, and sexuality—use these tools. This knowledge will help shape smarter, safer, and more equitable sex ed and health systems.

Further studies could also explore how AI tools might assist teachers and students in sex education. Beyond offering just information, they could provide teaching methods like quizzes, role-plays, or even full lesson plans.

But unlocking that potential will require a culture that welcomes sexual knowledge, rather than pushing it to the algorithmic shadows. It will also mean developing specialized tools trained on content vetted by experts.