Imagine facing a maze of obstacles every time you seek reproductive health services—this is a reality for many people with disabilities.

A revealing study of nearly 7,000 individuals in the United States assigned female at birth highlights the stark difference in healthcare accessibility between people with and without disabilities.

The findings reported in JAMA Network Open, a medical journal published by the American Medical Association, shed light on an urgent issue that demands attention and action.

“We’ve been seeing a lot of reports of inequities in reproductive health. There’s a maternal mortality crisis among Black women in the US; we’ve been seeing greater restrictions on abortion access across our country,” said Principal Investigator Margaret (Waru) Gichane, Ph.D.

“What’s often missing as we look at these inequities is what is happening to people with disabilities.”

Combating ableism in healthcare

To understand the barriers to reproductive health services, it’s crucial to understand ableism.

Ableism is the discrimination or prejudice against people with disabilities, favoring those who are not disabled.

“The social attitude toward assuming everyone needs to be able to walk to be included in society is disabling,” said Robin Wilson-Beattie, a disability advocate and reproductive health educator part of the research team’s advisory board.

Wilson-Beattie explains that the social model of disability identifies “social environment barriers, attitudes, and challenges as the defining characteristics of being disabled.”

“An example would be a wheelchair-inaccessible space, with steps preventing a person from entering the home or establishment.”

In the context of reproductive health, ableism upholds societal barriers and leads to subpar healthcare services and inaccessible medical facilities. It is characterized by insufficiently trained practitioners and biased treatment.

The study

Researchers examined the challenges faced by people with disabilities in accessing two reproductive health services: 1) Pap smears, a test for cervical cancer, and 2) family planning, including various birth control methods.

The nationwide study took place from December 2021 to January 2022.

Previous smaller-scale studies show this group encounters several hurdles. However, they did not reveal how pervasive obstacles are among people with disabilities or how they may differ based on disability type and status.

The study primarily assessed five types of barriers:

- Logistical Barriers: Trouble with transportation, getting time off work or school, and arranging childcare.

- Access Barriers: Difficulty finding a clinic that offers reproductive health services and feeling comfortable there.

- Cost Barriers: Issues with affording the services.

- Privacy Barriers: Privacy concerns due to the presence of caregivers or being forced to inform others about the pursuit of services.

- Interpersonal Relationship Barriers: Problems with family or partners not wanting them to go to the clinic.

Measuring disability

The study used eight indicators to assess disability based on questions from the Washington Group Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS). The WG-SS was developed by the Washington Group on Disability Statistics, an international body established under the United Nations Statistical Commission.

These questions ask respondents to evaluate the difficulty they experience in basic functional domains with the following response options: “no difficulty,” “some difficulty,” “a lot of difficulty,” and “cannot do at all.”

The researchers also examined different levels of disability to see how access to reproductive healthcare varies.

The 8 disability indicators:

- Vision: Do you have difficulty seeing?

- Hearing: Do you have difficulty hearing, even when using hearing aids?

- Mobility: Do you have difficulty walking or climbing stairs?

- Activities of Daily Living: Do you have difficulty with self-care, such as dressing or bathing?

- Communication: Using your usual language, do you have difficulty communicating, such as understanding or being understood?

- Overall Disability Status: A participant was classified as having a disability if they reported “a lot of difficulty” or “cannot do at all” in any one of the first five domains.

- Some Difficulty Functioning: While below the disability threshold, participants were still recognized if they reported “some difficulty” functioning in one or more of the first five domains.

- Multiple Disabilities: Identified participants who reported “a lot of difficulty” or “cannot do at all” in two or more of the first five domains.

The participants

The final group studied included 6,956 people assigned female at birth, with an average age of 36 years. About 8.5% of these participants were considered to have a disability related to hearing, vision, cognition, mobility, communication, or activities of daily living.

Compared to those without disabilities, a higher percentage of participants with disabilities were non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic/Latinx, identified as LGBTQAI, lived below the poverty line, and had experienced unfair treatment in medical settings.

Of those with a disability, 73.2% had at some point tried to access reproductive health services, with the rate being similar regardless of the overall disability status.

The results

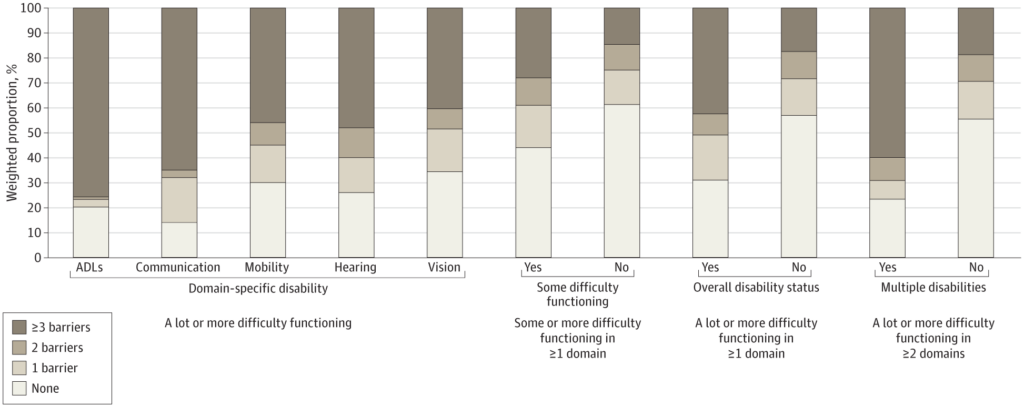

People with disabilities, especially multiple ones, were more likely to face hurdles receiving reproductive health services. Logistic and access barriers were most common.

“The biggest issues were getting time off work to go to an appointment and finding a place where someone felt comfortable,” said Gichane.

People who experience difficulties in activities of daily living or communication reported the most obstacles, with up to three-quarters encountering three or more of the five assessed barriers.

Compared to people without disabilities, those who reported some difficulty functioning generally encountered more barriers, with the exception of access barriers.

Participants with disabilities often struggled with practical issues, like getting transportation, taking time off from work or school, finding childcare, and finding a clinic that offers the services they need and where they feel comfortable.

People with disabilities also had trouble going to clinics if their family or partner didn’t want them to. Researchers suggested this could be due to relying on others for help with travel or facing more violence or control from a partner.

Limitations

The study did not address specific barriers such as the availability of accessible equipment, materials that work with screen readers, or sign language interpreters.

Additionally, the method for identifying individuals with disabilities might have overlooked those with chronic or mental health issues. It also excluded people living in institutions.

The authors emphasized the need to investigate these overlooked areas, including the impact of abortion bans.

Abortion access

This group was also more likely to consider managing an abortion themselves than people without disabilities. Qualitative studies could provide a more detailed and diverse understanding of why.

In the meantime, Wilson-Beattie’s own story offers insight into the backlash to abortion rights in the US.

“I had the unfortunate experience of getting an abortion in a state where it would now be illegal,” said Wilson-Beattie.

“I was denied the abortion based on the fact that I had a spinal cord injury with paralysis. I was forced to seek and find the only available doctor in the state who could do the procedure in a hospital. This added several weeks to the pregnancy.

“To add insult to injury, the physician was deliberately cruel (pretending to accidentally show me the ultrasound when I said no, as was my right) and sexually assaulted me by insisting on doing an unnecessary breast examination. I couldn’t complain, as I had no other options.”

Building an accessible future in healthcare

People with disabilities face considerable challenges accessing reproductive health services in the United States. There’s a pressing demand for improved transportation, language interpreters, and a shift toward patient-first healthcare.

Telehealth, which provides support over the phone or Internet, could significantly ease access for many.

It’s also important to pay extra attention to privacy and the possibility of coercion or abuse that might stop people with disabilities from getting care.

Making these changes is not just about meeting standards; it’s about enhancing inclusivity and equality in healthcare.