It’s time for sexual wellbeing to supercharge public health.

For too long, it’s played second fiddle and been confused with sexual health. But let’s set the record straight: sexual wellbeing isn’t just a piece of the sexual health puzzle.

Experts are calling sexual wellbeing a new pivotal concept: one that’s shaking up traditional ways of thinking and poised to revolutionize public health on a global scale.

Listen to this study covered by The Sex Science Podcast:What is sexual wellbeing?

A 2021 Lancet article titled “What is sexual wellbeing and why does it matter for public health?” lays the groundwork for defining sexual wellbeing on its own terms.

It was a collaboration between public health researchers Kirstin R. Mitchell, Ph.D., and Ruth Lewis, Ph.D., of the University of Glasgow, Lucia F. O’Sullivan, Ph.D., of the University of New Brunswick, as well as Dr. J. Dennis Fortenberry, MD MS, of Indiana University.

Unlike sexual health, which is generally focused on the prevention of infection and unplanned pregnancy, sexual wellbeing addresses broader dimensions of sexuality-related experience

Dr. Mitchell shared the following working definition of sexual wellbeing, which will be published in a forthcoming paper:

“Sexual wellbeing is about sexual emotions and cognitions which include feeling safe, respected, comfortable, confident, autonomous, secure, and able to work through change, challenges, and past traumas.”

The definition was developed along with a 13-item measure in preparation for the Wellcome-funded Fourth British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles.

“I see it as a concept that links sexuality on one hand, and psychological wellbeing on the other,” Dr. Mitchell said

The 4 pillars of sexuality in population health

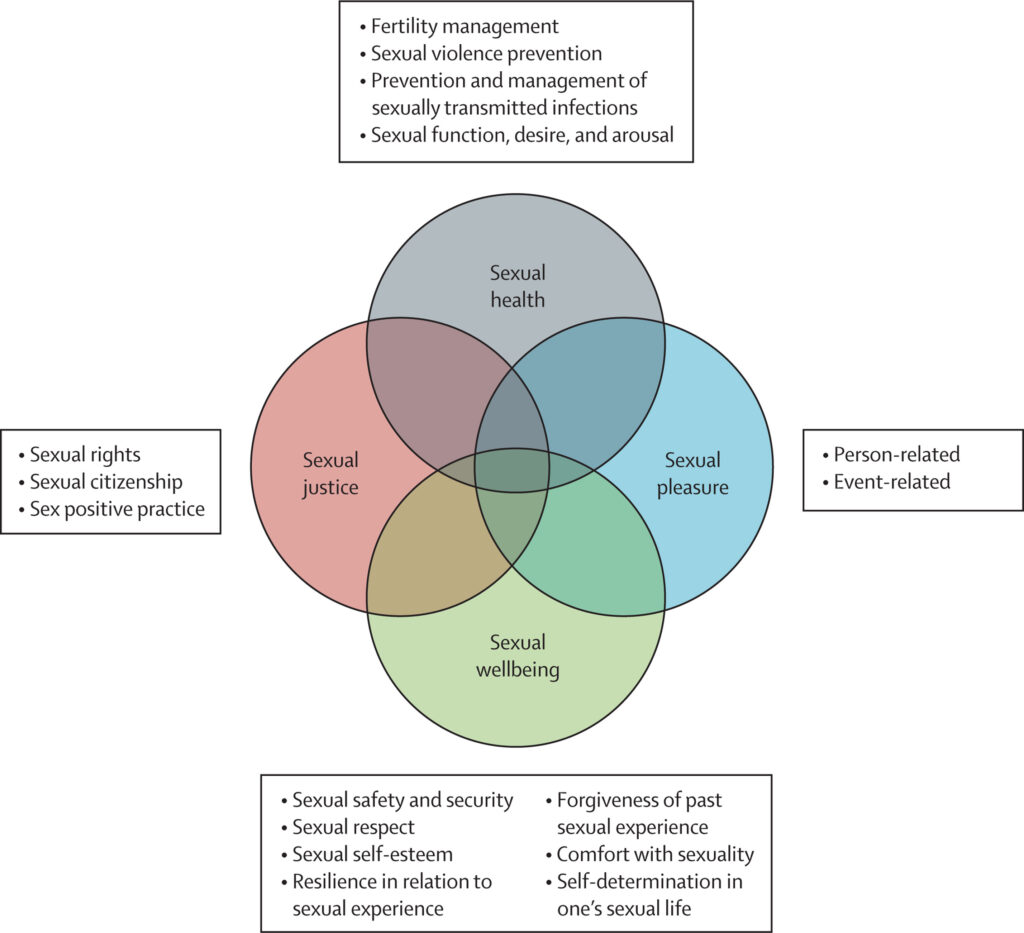

Sexual wellbeing is one of four distinct yet overlapping pillars of sexuality.

“Each pillar is strengthened by considering the other one,” Dr. Mitchell added. “If you’re trying to promote sexual health, you could do that more effectively if you’re considering sexual pleasure, if you’re promoting sexual rights, and if you are aware of sexual wellbeing as an explicit goal in itself.”

Together they form a foundation for achieving a holistic approach to public health.

- Sexual wellbeing: Connects to a person’s general wellbeing and how one views their past, current, and future sexual and intimate experiences.

- Sexual health: Focuses on fertility management, sexual violence prevention, management and prevention of sexually transmitted diseases (STIs), sexual function, arousal, and desire.

- Sexual pleasure: Involves various types of satisfaction, both physical and psychological, linked to sexual experiences related to individuals or specific events.

- Sexual justice: Refers to the necessity for everyone to get fair support and respect when it comes to their sexual and reproductive experiences, in terms of culture, society, and the law. This includes sexual rights, sexual citizenship, and sex-positive practices that address sexual trauma.

The 7 domains of sexual wellbeing

To provide a clear and meaningful understanding of sexual wellbeing, the researchers behind The Lancet paper pinpointed seven key areas that it covers.

- Sexual safety and security: Involves teaching sexual consent, preventing gender-based violence, and addressing risks to sex workers. When attained, individuals experience little worry about their future sex life, a lack of vulnerability during sexual activities, and feel safe with sexual partners.

- Sexual respect: Consists of educating about sexual rights of minority groups and interventions to reduce sexual harassment. When achieved, one’s sexual identity and preferences are accepted by social groups and the broader culture.

- Sexual self-esteem: Includes strategies to enhance overall sexual functioning and the ability to relate sexually with a partner. People with sexual self-esteem will feel good about their bodies sexually and in control of their sexual thoughts and desires.

- Resilience in relation to past sexual experiences: Comprises support for recovery of sexual trauma and reduces the negative effects of stressors faced by sexual minorities People with resilience likely have a trusted person they can speak to about their sex lives, whereas it may take others longer to recover from negative sexual experiences.

- Forgiveness of past sexual events: Programs to support recovery from sexual trauma are vital. Forgiveness extends to working through hurt caused by others and also forgiving oneself for any mistakes made in past sexual experiences. However, victims of sexual assault should never feel pressured to pardon others.

- Self-determination in one’s sex life: Consists of global public health efforts related to stopping unwanted sexual interactions and supporting women’s autonomy in reproductive choices. When gained, a person will only engage in sexual activities they really want to and not feel pressure from others.

- Comfort with one’s sexuality: Improved sexual communication is linked to better sexual health behaviors like contraceptive use and discussing sexual anatomy with healthcare providers and reduces feelings of sexual guilt. If attained, it leads to feeling focused during sex with a sense of flow, no unwanted thoughts, no shame about desires, comfort with identity, and a pleasurable sex life.

These seven domains were themselves based on specific criteria, such as the need for sexual wellbeing to be inclusive, distinct from related concepts (e.g., sexual health and pleasure), encompass one’s experience across lifespan, and tied to factors that can be improved through policies, public health efforts, medical support, or personal growth.

Why should public health prioritize sexual wellbeing?

The authors identified four main reasons why sexual wellbeing is a worthy goal for public health.

They argue that sexual wellbeing can show whether different groups have equal access to good health. Observing it can help spot problems such as discrimination, violence related to gender and sexuality, racism, and the risk of getting STIs or HIV.

“I see it as fundamentally opening new ways of looking at inequities by sexual minority groups’ experience,” Dr. Mitchell said.

“If you ask them about their self-esteem in relation to sexuality, whether they feel their rights are respected, whether they have access to resources, whether they feel comfortable— it’s a much richer way of understanding where inequities creep in and how they can constrain or shape people’s experiences if they are.”

Evaluating sexual wellbeing also provides valuable insights into population wellbeing. A 2012 Belgian population study shows that integrating the concept into overall wellbeing assessments is not only feasible but improves understanding of how perceptions of wellbeing evolve with age.

In fact, Dr. Mitchell and Dr. Lewis are working with the Scottish Government to help bring together expert opinions from clinicians, researchers, and policymakers on how to advance sexual wellbeing as a priority within the national strategy. This includes setting both short-term and long-term goals for a national wellbeing strategy.

Tracking sexual wellbeing can also reveal important population trends distinct from sexual health. Take the French, for example. Surveys spanning 40 years found that more women and men began thinking that having sex was essential for feeling good about themselves. It went up from 48% to 60% for women and from 55% to 69% for men, from the 1970s to 2006.

Lastly, accepting sexual wellbeing as a driving force in public health innovation is a way to confront the deep-rooted causes of sexual inequalities. This shift refocuses the view that sexuality is strictly a private matter.

“It’s not normalized, to say, ‘How’s your wellbeing, how’s your social wellbeing, your educational, your sexual wellbeing.’ We just miss it out of those conversations,” Dr. Mitchell said.

“Another hope is that by talking about sexual wellbeing, we can start to include it in those general conversations about mental health and wellbeing and it’s not just siphoned off as something that’s just for sexual health practitioners or researchers.”

Moving forward

Beyond our basic biological needs, let’s move past limiting notions and finally embrace a holistic perspective to human sexuality: sexual wellbeing is at the core of our lives and happiness.

Despite the hurdles we may face, it’s high time to kickstart sexual wellbeing within public health.

Our work is cut out for us.

As we redefine public health, we’ll need clear goals and smart strategies, driven by solid data.

We’ve also got to invest where it counts most, meeting people’s basic needs, no matter who or where they are. To do so, we’re relying on healthcare professionals to acknowledge the importance of sex-positive and trauma-informed approaches.

Yes, the road ahead may be challenging, but that’s where the adventure begins. This new way of weaving sexual wellbeing into public health isn’t just about changing how we handle sexual issues and inequalities—it’s about crafting a brighter, healthier future for everyone.

Featured Image Source: AI-generated with DALL-E